The opening of Britain’s first generation tramways was often marked by a period of civic celebrations. This is not so surprising given the transformative impact they were to have on people’s mobility, and also the very size and layout of Britain’s towns and cities themselves.

Likewise, when the era of cheap, convenient and reliable public transport that they ushered in finally came to an end, a century of so later, many of Britain’s remaining tramways again marked the occasion. This often took the form of a “last tram” week, which frequently unleashed a wave of public affection and nostalgia. In Glasgow, for example, it is estimated that one quarter of a million citizens – about one quarter of the population – turned out to bid their trams farewell.

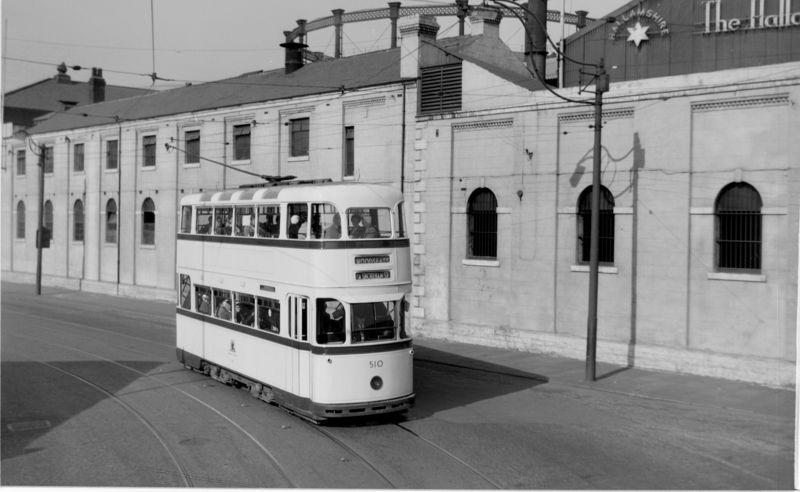

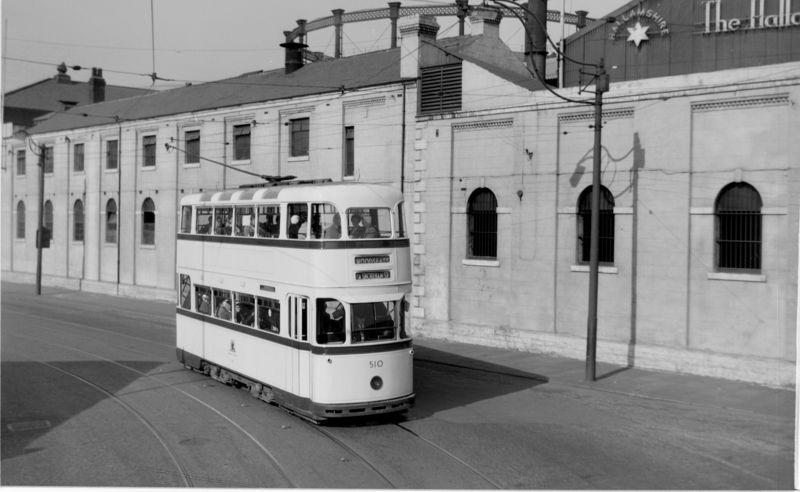

To mark the occasion of Sheffield’s Last Tram Week, two of its newest tramcars (510 & 513) were specially decorated for the occasion. Together with an older illuminated tramcar, they formed part of the closing procession of assorted tramcars on Saturday 8th October, which was watched by thousands of Sheffield citizens despite the pouring rain.

Sheffield was not only the last English city to give up its trams but had for many years been one of the staunchest supporters of this form of transport. So, despite the heavy losses to its tramcar fleet as a result of war-time bombing and associated deprivations it went to great lengths in the immediate post-war period to replenish its chronic shortage of trams.

Many other cities (Leeds, for example) made good their losses by purchasing second-hand tramcars from other operators, many of which were in the process of abandoning their trams. Sheffield, however – almost uniquely – commissioned and purchased a brand new batch of post-war trams to replenish its depleted fleet.

Sheffield 510 – one of the two decorated “last” trams – was a product of that endeavour. By the time the war was over, Sheffield transport department – which celebrated its golden jubilee year in 1946 – was facing a chronic shortage of trams since 93 cars out of a nominal fleet of 468 trams were not available for service. Moreover, post-war restrictions prevented the department from building further cars of its own as it had in the past.

In spite of these obstacles, the department nevertheless managed to produce a brand new prototype tram – Jubilee 501, which was built to a radically different design – by pressing into service materials they already had in stock.

The much more streamlined profile incorporated a number of new features including an innovative 9-foot wheelbase truck with rubber mountings and a novel form of interior lighting using fluorescent tubes together with the latest folding entrance and exit doors. In other respects the car body resembled that of its predecessors in being timber-built, though this posed a problem as the Ministry of Transport refused to authorise the new timber that would be required for subsequent production models.

M J O’Connor, 2/10/1960.

To get round the problem, the department accepted a tender for 35 new trams that shared a similar body style to the Jubilee prototype but utilised steel pillars and framing together with aluminium panels as an alternative to the more traditional timber construction.

The cars were supplied by Charles Roberts of Wakefield, who had previously specialised in the manufacture of railway wagons but had recently diversified into the construction of bus bodies and so were able to incorporate a similar construction technique for the new trams. Production models also featured another innovative feature – resilient drive gears – that contributed to the near silent running of the vehicle.

510, Neepsend Lane. M.J. O’Connor, 29/9/1959.

The first of the new tramcars – including 510 – was delivered in 1950 though the last of the batch was not completed until April 1952. Sadly, however, by this stage the writing was on the wall for the last of England’s major urban tramways since a combination of rising infrastructure costs, post-war redevelopment plans and growing concerns over increased traffic congestion contributed to the decision to inaugurate a tramway replacement programme.

510, Firth Park terminus. M.J. O’Connor, 1956.

The original closure date was to have been 1 April 1966, but in the event the bus conversion programme was speeded up to such an extent that the last trams actually ran in dismal weather conditions on Saturday 8th October 1960, by which stage the newest of the ‘Roberts’ cars were barely eight years old.

All but two of these were unceremoniously scrapped, but number 510 was donated to the tramway museum at Crich, where it has been preserved in its splendid ‘Last Tram week commemorative livery as a poignant reminder of a once ubiquitous and familiar mode of transport.

After spending over 30 years in service in Crich as part of the regular passenger fleet, which comfortably exceeds the decade it spent in its native city, the tram was withdrawn with a truck defect in 2006. By this stage it was in need of a major overhaul which has recently been completed in the workshops at Crich, funded by the Tramcar Sponsorship Organisation.

This overhaul included a full repaint in the special “Last Tram” livery, thanks to a vote of the TSO membership, who were asked to choose between this and the regular Sheffield livery that is exhibited by Sheffield no. 264. This standard livery can also be seen on a second surviving Roberts car – no. 513 – that belongs to Beamish Museum but is currently on long-term loan to the East Anglia Transport Museum in Carlton Colville.

Following its overhaul, 510 was ceremoniously welcomed back into the operating fleet in 2014 as part of a week’s celebrations commemorating Sheffield’s contribution to Britain’s tramway history.

Sheffield 510 being turned round at Glory Mine terminus on 21/9/2019. Photo: Jim Dignan.

The only other preserved British tramcar to display a “Last Tram” livery is Liverpool’s 293, which currently resides @ Seashore Trolley Museum in the USA. This makes 510 a highly significant, even though somewhat atypical, addition to the collection at Crich.