The first mechanically powered trams to challenge the early dominance of horse trams relied on steam traction, though they were prevented by law from operating on public highways until 1879. A change in the law in that year opened up a short-lived boom in steam tramway-building during the 1880s, a decade in which no fewer than 45 new steam-powered tramways were opened.

One of these was the Manchester, Bury, Rochdale and Oldham Tramway, which opened an extensive steam-powered tramway covering a number of urban areas to the north and east of Manchester in 1883. Unfortunately it never reached Manchester as this would have involved running over the existing horse tramways of the Manchester Carriage & Tramways Company, and the necessary permission was not forthcoming. Nevertheless for a time following its completion in 1884, the company operated the largest steam tramway undertaking in the world (at 33¼ miles).

MBRO 84 was one of a batch of four similar steam tram engines to be ordered from Beyer, Peacock (numbered 83 to 86). These four locos were part of a larger order of 26 new locomotives that were purchased from the same company in 1886. By this stage, however, the tramway operation was experiencing severe financial difficulties and less than a year later the company had crashed, leaving Beyer, Peacock as the largest creditor.

Fortunately, this was not the end of the tramway as a rescue deal was put together resulting in the operations being taken over by a new company (the Bury, Rochdale and Oldham Tramways Company), which persisted until it was taken over during the early days of municipally operated electrically powered tramways by the various local authorities through whose areas it ran.

Rather unusually, the MBRO tramway operated on two different gauges. Narrow gauge (3’ 6”) sections ran through the narrow streets of Rochdale and Bury, while a standard gauge section ran from the Rochdale boundary at Summit through Royton to Oldham then along Ashton Road to Hathershaw.

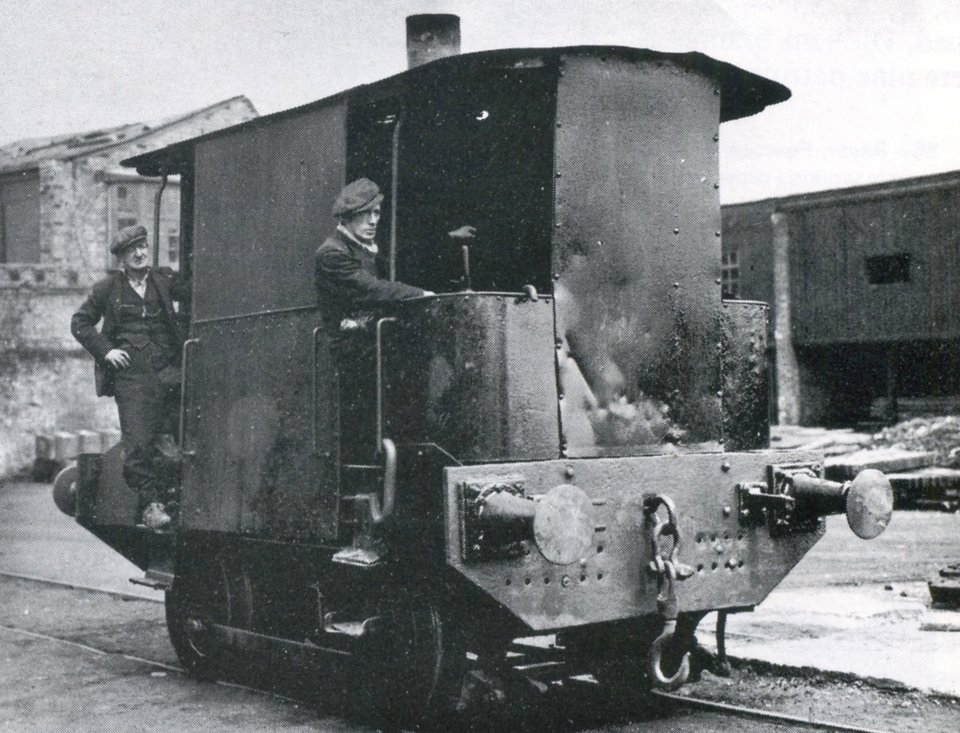

MBRO 84, Royton depot yard, 1900. Science Museum, Whitcombe Collection.

MBRO 84 was built as a standard gauge ‘heavy’ locomotive and cost £1000 when new. The tram engine incorporated a Wilkinson patent exhaust steam superheater”. The locomotive had a vertical steam boiler, the exhaust steam from which was fed back into a superheating chamber in the firebox. The steam superheater was designed in order to meet the legal requirement prohibiting the escape of any visible exhaust smoke or steam.

It is considered to have been among the most successful Wilkinson engines ever produced, though this was arguably because it was also fitted with the Kitson arrangement of roof condensers to minimise the visible emission of exhaust steam (as required by the Board of Trade regulations for steam trams). .Another legal requirement was the fitting of a ‘skirt’ or screen to enclose all working parts down to a level four inches above the roadway.

No.84 has much in common with the museum’s other Beyer Peacock steam tram engine, New South Wales 47. Unlike the latter, however, which was a much larger export vehicle that was originally designed and built for a very different operating environment in Australia, MBRO 84 was a much more typical example of the kind of steam tram engines that worked on the many steam tramway systems operating in Britain during the brief heyday of steam traction in the closing decades of the nineteenth century.

On 18th October 1893 the locomotive suffered a serious boiler explosion that resulted in the death of its driver and prompted in an investigation and report by Board of Trade Inspectors ten days later.

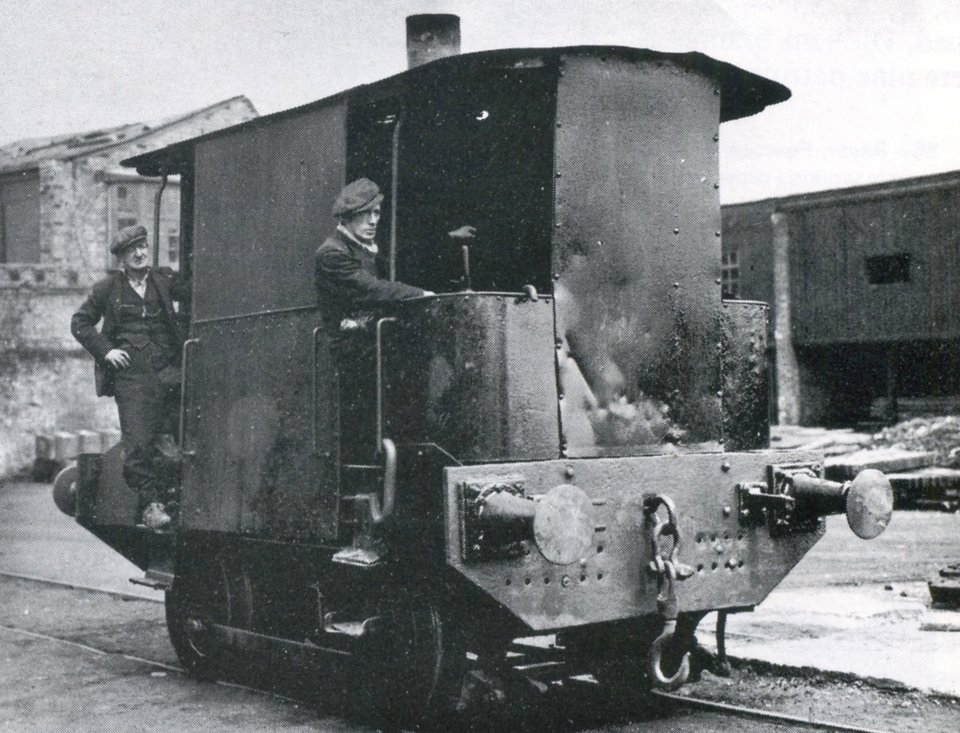

After spending the tramway part of its working life on the line running through Royton and Oldham No.84 was one of three Beyer Peacock-built Wilkinson tram engines that were sold for £50 apiece to the Ince Forge Company of Wigan following the demise of the tramway in May 1904. After their sale, the three ex-tram engines were modified in various ways to render them more serviceable as industrial steam railway locomotives. Thus, the skirting was removed and buffer plates were added at each end, to enable railway-style buffers to be affixed so that they could be used for shunting wagons.

MBRO 84, now converted into a small industrial railway locomotive at the Ince Foundry. W.G.S. Hyde.

Other adaptations required for street running that were removed at the same time included the roof condensers and the exhaust steam superheater. Essentially, the tram engines were shorn of most of the sophisticated devices that were required by law for vehicles that were allowed to run on public roads and were converted instead into relatively unsophisticated industrial steam engines.

As for their subsequent history, it is believed that No. 84 had its boiler rebuilt in 1930 though it is not known how extensively; and it is also known that by this stage this was the only one of the three original locomotives to remain in service. Indeed, it continued in service with the same firm until February 1954.

By this stage, the original Ince Forge had been taken over and the remaining ex-steam tram was destined to be scrapped but fortunately, in view of its historical significance, the new owners were persuaded to present it for posterity to the British Transport Commission. Since that time, the tram engine has undergone a somewhat chequered career in the course of which it has travelled around the country, undergone some attempts at restoration and also suffered some loss of its remaining equipment.

It was initially stored for a time at the Crewe Locomotive Works and is thought during this period to have lost the brake gear that had been attached to one set of wheels while it was in use at Wigan. The engine was then stored at a number of other locations around the country, possibly including the former Pullman Car works at Preston Park in Brighton but this period of its existence is still shrouded in some uncertainty.

MBRO 84 in a partially dismantled state, Dinting Railway Centre in Glossop. Paul Abell.

Ownership of the tram engine subsequently passed to the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester (MOSI), which loaned it to the Dinting Railway Centre in Glossop. There it was dismantled by members during the 1970s in preparation for an intended restoration project. Some progress was made including the preparation of drawings for the tram’s main frame plates, which were also manufactured locally.

After this promising start, however, Dinting Railway Centre closed down in 1991, resulting in the transfer of 84’s now dismantled remains to the MOSI premises in Manchester. Some time later, MOSI contacted the National Tramway Museum in 2002 with an offer to donate what was described as “a steam tram on 10 pallets” and, equally importantly, copies of the general arrangement drawings for the tram engine which illustrate the various components.

This offer was accepted with enthusiasm and the main components – which are incomplete, though they do include the replacement side frames from its days at Dinting – were relocated to the museum’s off-site storage facility. Since then a start has been made on cataloguing and compiling an inventory of the various components which would be an essential prerequisite for any future restoration project. Unfortunately the missing parts include the wheelsets, so replacements for these would obviously be a major requirement.

In the course of this examination questions have been raised as to whether this tram engine really is no. 84 or one of the other three from the same batch. One problem is that as the makers’ plates were removed at the time of their sale to Ince, it is impossible to be certain of this.

Moreover, while numbers relating to the three other trams from the same batch have been found stamped on various components, none of them feature the number 84, suggesting that, if nothing else, a considerable number of parts from the other locos were used to keep No.84 running.

In a strategy review undertaken in 2014, the restoration of MBRO 84 as an operational tram engine was identified as a priority aim. If it could be achieved it would, in theory, be possible to demonstrate an authentic British steam tram in operation together with a typical steam trailer – Dundee 21, which is also in the collection – though this would also require some additional work in order to return it to operational condition.

Restoring the steam tram engine and trailer are daunting tasks in themselves but would also require some additional extensive supporting infrastructure. At the very least, a separate engine shed would be needed, in which to house the steam tram well away from the rest of the collection since steam tram operation also entails the need for somewhere to empty and safely dispose of the hot ashes that are produced each time the engine is fired up. This is an operation that could not safely be conducted in the vicinity of mostly wooden bodied electric or horse trams.

Nevertheless such an ambitious project offers the tantalising prospect of the recreation of a forgotten era in Britain’s tramway history. More than that, it would afford the unique possibility of demonstrating once more the three principal modes of tramway traction – horse, steam and electric – together on the same site.

Simultaneous operation of all three modes of traction was achieved for a time in the mid-1980s while the museum’s other steam tram – John Bull – was still in active service, but has not been possible since that time..