Number 10 was one of two additional cars ordered from G.F. Milnes & Co. shortly after the opening in 1901 of the five and a quarter mile long Hill of Howth tramway, which was situated on a rocky promontory to the north-east of Dublin. For most of its life the tramway was operated by the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) and, by the time of its closure in 1959, was the last one left in Ireland.

The tramway itself led a somewhat precarious existence since the receipts that were mostly generated by the tourist traffic to the hill’s 560 foot summit were insufficient to cover the interest charges on the initial capital construction costs. Despite this handicap, it somehow managed to keep going for some 30 years after its closure was first mooted, possibly because it was seen as a way of providing more customers for the company’s railway operations.

The rationale for purchasing Hill of Howth 10 and its stable-mate number 9 is not entirely clear either, since the tramway managed to function for most of its existence with the original fleet of 8 cars. The newcomers were not only largely surplus to requirements but in many respects were also singularly unsuitable for the system as their extra length and absence of cross-springs between the bogies made them much more prone to derailment than the rest of the fleet.

Consequently, they were only rarely allowed down to Howth itself and for many years were largely reserved for peak traffic periods. Because they were so little used, both cars still retained their original chilled-iron wheels dating back to 1902 at the time the line closed over half a century later.

10 at Sutton. M.J. O’Connor, 31/5/1959

In terms of its design and specifications, Hill of Howth 10 is one of the more idiosyncratic tramcars in the entire Crich fleet, partly on account of its somewhat broader gauge (originally 5’ 3”), but also because of its unusually large external dimensions. At 32’ 8” long and 7’ 6” wide, the tramcars were true leviathans and their somewhat ungainly appearance was exacerbated by having the motors mounted outside the axles, which made them rather unbalanced.

Number 10’s seating arrangements are also unconventional, especially in the downstairs saloon, which combined back to back longitudinal benches arranged in knifeboard fashion down the centre of the car together with a fixed pair of transverse seats on either side of the doors. It has been suggested that one explanation for this curious arrangement is that Howth 10’s interior saloon was designed by the GNR’s railway works in Dundalk and that, in effect, it resembles three compartment-style railway carriages (i.e. with no linking corridor) that have been reconfigured as a single tramcar saloon

Whatever the explanation for its unusual configuration, such an arrangement must have made it almost impossible for conductors to collect the fares without treading on passengers’ toes. When first introduced, the unglazed downstairs windows were equipped with wire safety screens and striped canvas blinds, which would have ruled out any compensatory sea views. Fortunately the cars were glazed in 1908, though relatively few passengers would have benefited from this because of their infrequent usage.

10 at Summit. D.K.W. Jones, 11/8/1958.

The layout of the platforms was also unusual in that they were equipped with four entrances since the usual double entrance on the right of the motorman was augmented with an additional single entrance immediately ahead of the saloon on the left, each of which was equipped with folding gates. Since these additional entrances were seldom used they eventually became stuck in the closed position, held fast by many coats of red lead paint. These additional entrances did reduce the space available for the stairs, however, which, as a result, were exceptionally steep and awkward to mount.

Another unfortunate feature of the tramcar was a propensity to become ‘dewired’ as a result of a design fault with the trolley boom, added to which was a tendency for trolley ropes to become entangled with the upper deck wire screens unless conductors were careful to stand well out from the tramcar while turning the trolleys.

10 and 9 passing. M.J. O’Connor, 31/5/1959.

With so many peculiar features and operational foibles, it is perhaps not surprising that number 10 and its sister car were destined to become the white – or rather teak – elephants of the system. Indeed the only advantage they had over the rest of the fleet was their relatively greater speed, provided they could be kept on the rails and in contact with the overheads!

Very occasionally this gave them the edge over their rivals though, one rare instance being a downhill run by sister car number 9 (on 30 May 1959), which just managed to make it to Hill of Howth station in time for a very tight rail connection. By this stage, cross springs had been fitted between the bogies and this improved the performance of the two tramcars to such an extent that, rather ironically, they were in heavy demand for the operation of ‘special’ tours for tramway enthusiasts during the twilight years of the tramway.

A more remarkable achievement is that both number 10 and its twin managed to survive into preservation while so many more successful and once ubiquitous tramcars from much better known systems passed into oblivion. Almost certainly they owe their good fortune in this regard to the fact that the Hill of Howth tramway was one of the last in the British Isles to close and, by the time it did so (on 31 May 1959), the nascent tramway preservation movement had already come into being and was able to ensure that at least some first generation tramcars could be saved for posterity.

Fortunately, in Hill of Howth 10’s case, this included one of the more colourful and quirky examples from this era. Meanwhile, its sister car (number 9) has been preserved at the National Transport Museum of Ireland in Howth, while a third tramcar from this remarkable system – number 4 – is preserved at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum in Northern Ireland.

As for Howth 10’s rather unusual teak-coloured livery, this was not its original colour scheme since the entire fleet was initially turned out in crimson lake and ivory. During the first world war the pigments that were required when the trams required a repaint became scarce and so ‘scumble’ was used instead for all the trams and railway rolling stock, an effect that was referred to as “grained mahogany” though it is often called “the teak livery”.

10 and 6 at Summit. D.K.W. Jones, 11/8/1958.

This replacement livery survived on the rest of the fleet until 1930, when the GNR introduced Oxford blue and cream rail cars and adopted the same livery for the ‘regular’ tram fleet, but because they were so infrequently used, numbers 9 and 10 retained their replacement ‘teak’ livery until the closure of the tramway.

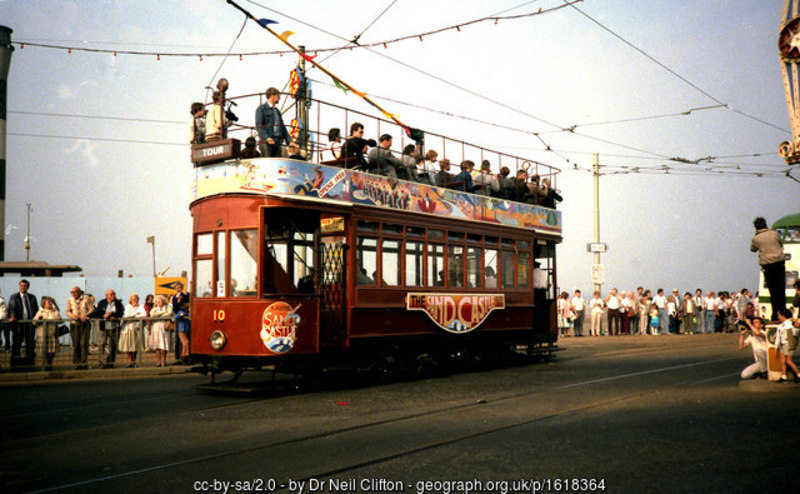

Howth 10 arrived in Crich in January 1960 and spent some time in storage between May 1971 and February 1985. Although the tram has continued to lead a largely sedentary life while in preservation, this hasn’t always been the case. One notable exception occurred in 1985 when the car was sent to Bolton to be fully restored and also regauged in order to take an active part in Blackpool Tramway’s centenary celebrations of that year. Indeed, it remained at Blackpool for the next five years and only returned to Crich in November 1989.