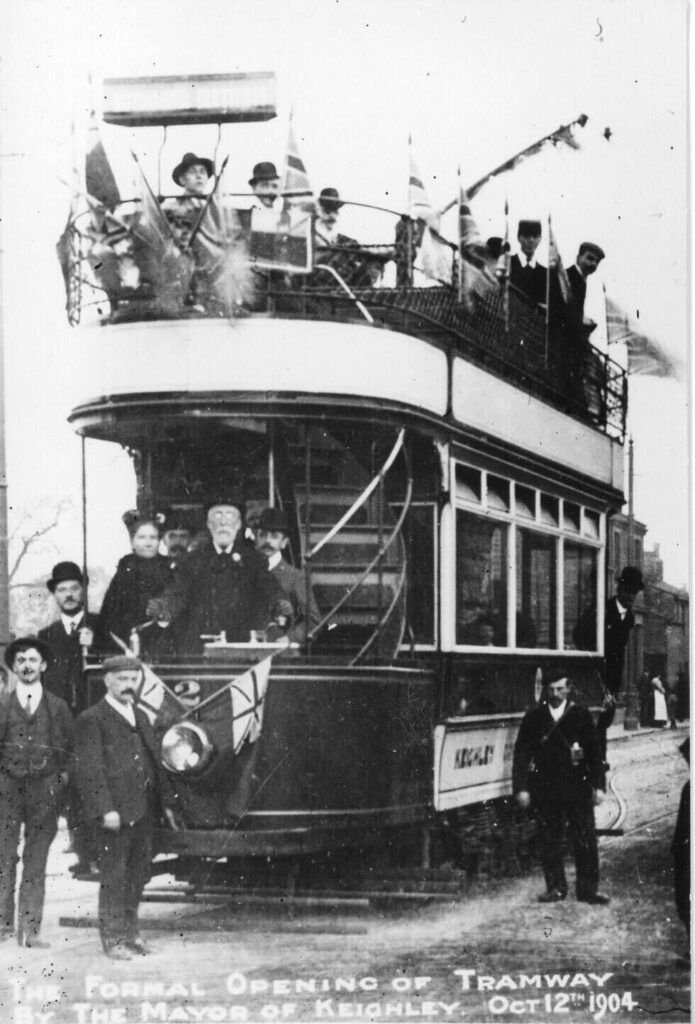

17th December 2024 marks one hundred years since Keighley Corporation entered the history books as the first municipally owned electric tramway to cease operations. This was just over twenty years after electric tramcar services had commenced there on 12th October 1904.

Image 1: The opening ceremony of Keighley Corporation Tramways, performed by the Mayor of Keighley on 12th October 1904, celebrated with a decorated tramcar (National Tramway Museum collection).

In truth, the Corporation had often seemed somewhat lukewarm in its attitude towards the tramway for much of its brief existence. After first taking control of the Keighley Tramways Company’s 4-foot gauge horse-drawn tramway in November 1896, when the loss-making company was faced with bankruptcy, the corporation initially agreed to buy the track for a nominal sum and lease it back to the company, paying an agreed price per horse per week to continue providing the service.

This arrangement lasted for five years, during which time the corporation obtained Parliamentary approval to convert and extend the horse tramway in 1898. It subsequently bought out the declining company’s remaining assets in September 1901. This surprising generosity on the part of the Corporation may or may not have been linked to the fact that many of those involved with the company were themselves also councillors.

However, the Corporation was only prompted to exercise its powers to convert the tramway to electric traction when a rival operator appeared on the scene in 1902. The Mid-Yorkshire Tramways Company had published grandiose plans for a regional ‘super-tramway’ network, linking several of the West Yorkshire townships including Ilkley, Otley, Shipley and Bingley, as well as Keighley itself. These proposals never came to fruition as the debt-laden company went into administration early in 1904.

Nevertheless, the threat of competition was sufficient to spur the Corporation into action and, after starting the conversion process in February 1904, the first electric tramcar services began later that year on 12th October. The occasion was marked by a formal civic opening ceremony.

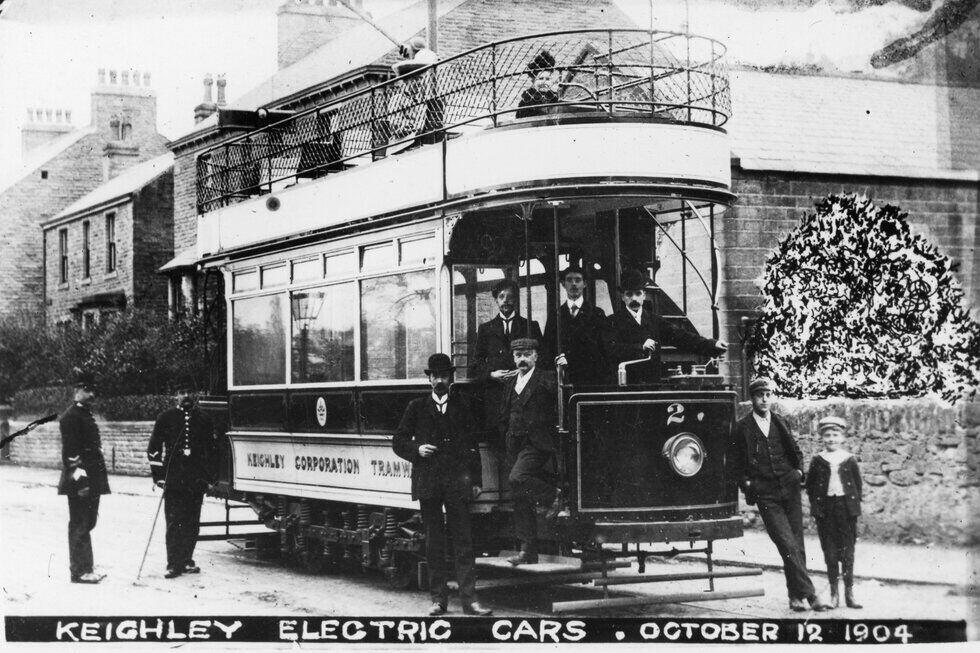

Image 2: A more informal pose was adopted for open-topped tramcar no. 2 later in the day, after the decorations had been removed (National Tramway Museum collection)

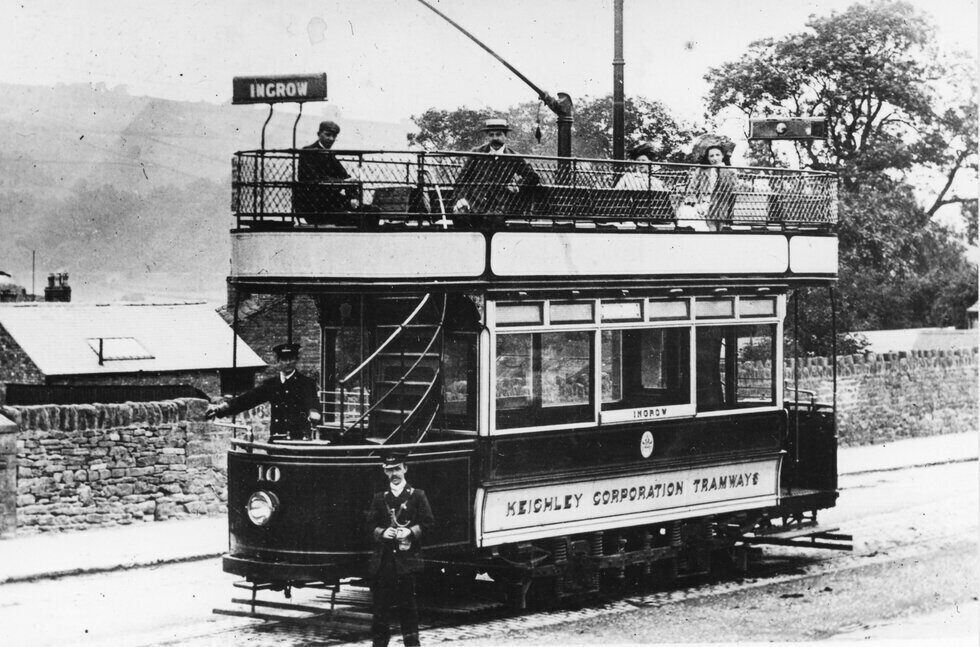

A short extension to Stockbridge was opened four months later, at which point the small tramway reached its maximum extent of 6.62 miles with three lines converging on the Keighley Mechanics Institute in the centre of the town.

The initial fleet of eight open-topped tramcars was supplemented by another two in 1905, followed by a further two balcony cars in 1906. All were supplied by Brush Electrical Engineering Company and were turned out in a crimson and white livery.

Image 3: One of the two new tramcars ordered for the Stocksbridge extension – number 10 – is pictured at the Utley terminus with the driver at the back of the tramcar, ready to depart in the opposite direction for Ingrow (National Tramway Museum collection).

After its slightly tentative start, the Tramway’s manager was rather embarrassingly dismissed in May 1905 after an ‘amorous episode’ was alleged to have taken place in his office. In other respects, the tramway settled down to an untroubled and – unlike its predecessor – reasonably profitable existence. In its early days, dogs were not allowed to ride on the trams, being encouraged to trot along behind the vehicle instead. This changed in 1908 when they were allowed to accompany their owners on the upper decks on payment of a 1d fare.

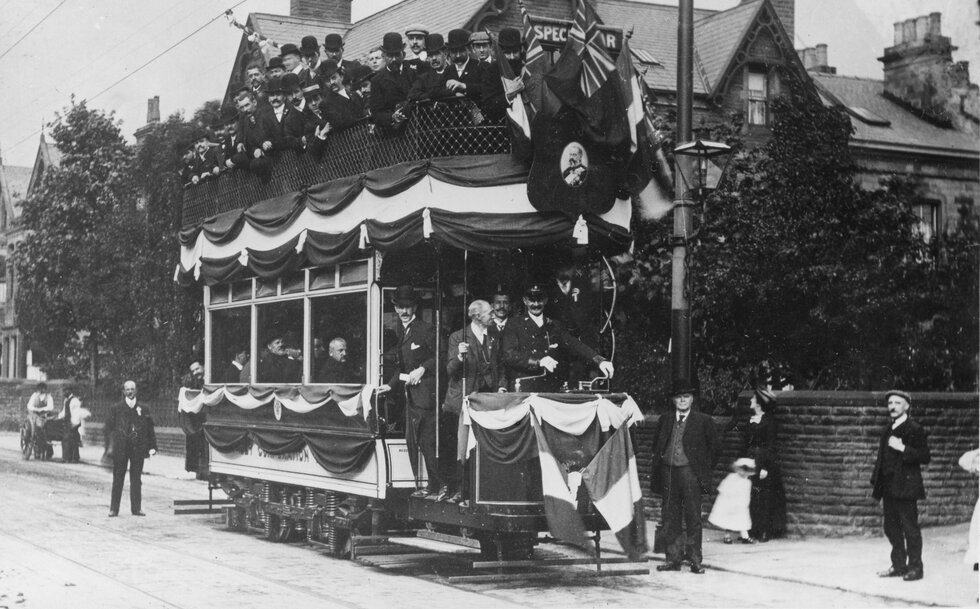

Image 4: An elaborate ceremony was held for a visit by an official French delegation on 3rd September 1905, featuring a decorated car at Holker Street, Keighley. New Tramways Manager, Mr. Bamber, is standing on the steps with his umbrella (National Tramway Museum collection).

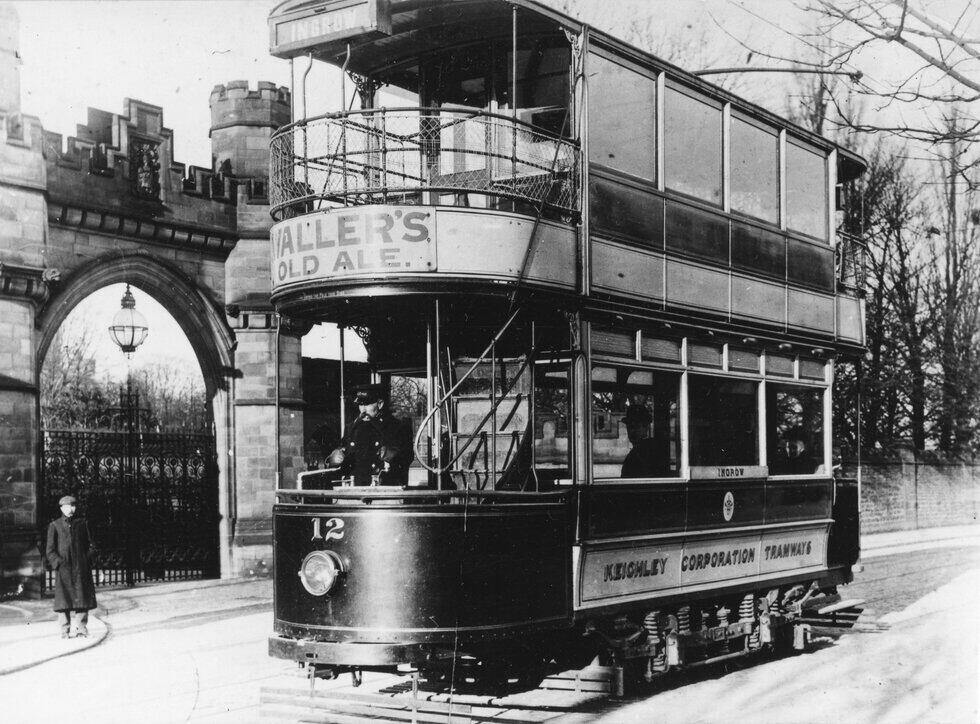

Image 5: The final tramcar in the Keighley fleet – no. 12 – photographed after its arrival in 1906 by the gates to Cliffe Castle in Keighley. Together with its sister car no. 11, these were the first cars in the fleet to have top covers. They were also rather unusual in having four top windows on each side but only three on the lower deck (National Tramway Museum collection).

Further extensions to the system were contemplated, but rejected on the grounds of cost. Instead, the corporation embarked on a series of alternative forms of traction, starting with the acquisition of petrol-driven motor buses in April 1909. These were intended to operate both within and outside the borough itself. This venture proved unsuccessful, however, partly on account of the vehicles’ primitive technology but also because they couldn’t cope with the deplorable state of the roads at the time.

Image 6: One of the first two Commer petrol driven buses acquired by the Corporation in 1909, pictured at Steeton Top. Photo reproduced from T.M. Leach (1999), Trams and Buses of Keighley in Old Photographs (Hendon Publishing).

Still keen to extend the tramway to neighbouring settlements, the Corporation then obtained powers to introduce trolleybuses – then known as ‘trackless trolleys’. This followed in the wake of Leeds and Bradford, which had introduced them to Britain for the first time on 20th June 1911. These used a conventional current collection mechanism consisting of two horizontally parallel overhead wires feeding current to the vehicle via twin spring-loaded rigid trolley poles.

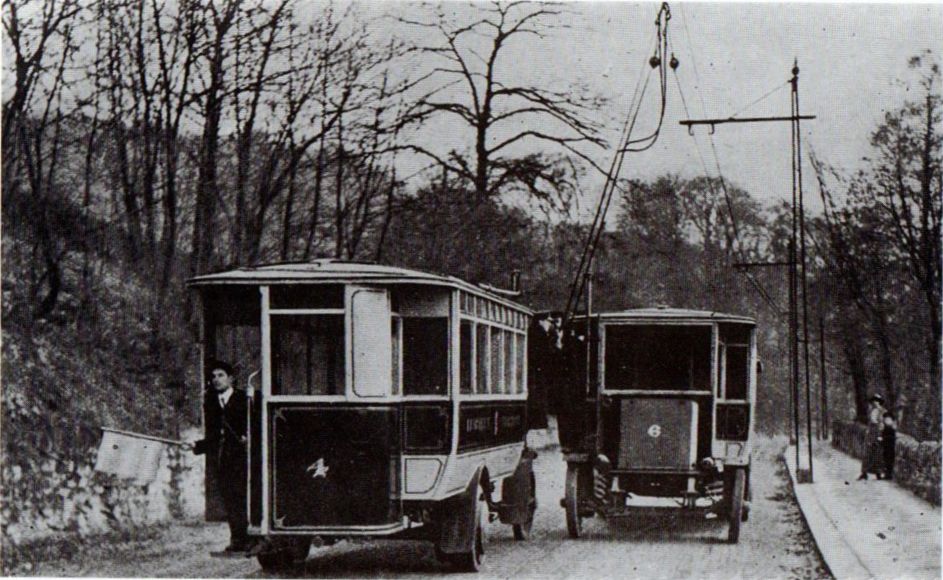

Unfortunately for Keighley Corporation, the system it decided to adopt in 1912 used a novel form of propulsion – the Cédès-Stoll system – that had been devised by an Austrian manufacturer. This turned out to be a disaster for various reasons. The technology was unreliable and inconvenient, relying on a detachable trolley, which ran along two overhead power lines and fed power down a flexible cable to the vehicle’s motors, which were built into its rear wheels. Because there was only one set of wires, Cédès-Stoll trolley buses travelling in opposite directions had to stop to exchange trolleys before either of them could proceed. Moreover, the trolleys themselves were apt to break loose, leaving the bus stranded without power while they continued to follow the wire downhill until they could be retrieved.

Image 7: Two of the Cédès-Stoll trolley buses pictured at Hawkcliffe Wood. The conductor waves a warning flag from the rear of trackless no. 4 while its driver exchanges trolley cables with the driver of no. 6. Photo: “Transport World” as published in J.S. King (1964), Keighley Corporation Transport.

Another problem was that the trolley buses were not much better at coping with the poorly surfaced road than their petrol engine predecessors had been. The jolting of the wheels caused the motors to run hot within their confined casings.

Quite apart from these foreseeable issues that might have been anticipated by a more rigorous assessment process, an even bigger stumbling block was that, with the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, the government shut down the British arm of the Austrian manufacturer, leaving the Corporation without access to spares or expertise in maintaining the vehicles. Consequently, by the end of the First World War, 9 out of the 10 available vehicles were out of action.

During the war, however, Keighley was one of the more progressive tramway operators. Women were recruited to serve as conductresses, motorwomen and, possibly even, an inspectress, to replace the male employees who had been drafted into the armed services.

After the war was over, most of the track was in urgent need of replacement following years of neglect. However, instead of investing in this (admittedly expensive) commitment, the Corporation rather bizarrely poured further resources into the trackless trolleys by vainly trying to improve their reliability and even erecting further overhead wiring (to Oxenhope), despite the state of the network. By this stage the Cedes-Stoll system had incurred a deficit of £22,701 between 1916 and 1924, while the tramway had incurred a more modest deficit of £816 between 1914 and 1924.

It was not until 1923 that the Corporation finally bowed to the inevitable by starting to rebuild various roads. In July 1924, powers were obtained to close and convert the tramway. The abandonment programme took place in stages, one line at a time, with the official closure (for the Ingrow line) being designated for 13th December 1924. Despite this, trams continued to run peak-demand workmen’s services for several more days until the final closure of the tramway took place on 17th December 1924.

Image 8: The first electric tram route to close was the one bound for Utley, which took place on 20th August 1924. Before that happened, the line had been reduced to single track while the other track was lifted and associated roadworks were carried out. In this photograph, car no. 4 approaches the disruptive roadworks outside the Roebuck Inn, not long before closure, while a commercial vehicle passes by on the other side of the road (National Tramway Museum collection).

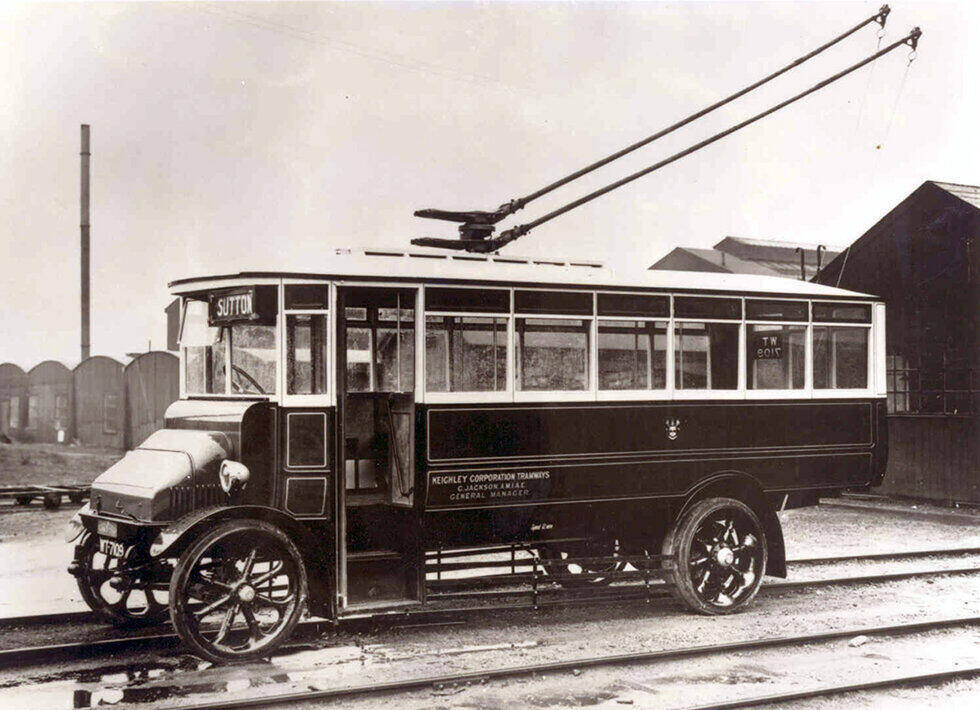

A fleet of more modern and serviceable ‘twin boom’ trolleybuses was purchased to replace the worn-out trams and (by now obsolete and decrepit) Cedes-Stoll vehicles. These only lasted for just short of a further eight years.

Image 9: One of the trolleybuses purchased by Keighley Corporation in 1924 to replace its worn out tramcars and unserviceable Cedes-Stoll trolleybuses was this vehicle – a Brush-built 32-seater body mounted on a Straker-Clough chassis with BTH electrical equipment and a BTH 247 40hp motor. Number 12 (registered as WT 7108) with its vertically mounted trolley poles only lasted in service until 1931, when Keighley Corporation ceded control of its municipal transport operations to West Yorkshire Road Car Company. The body and chassis ended up as a holiday home in Grassington for many years before it was acquired by Beamish Open-air Museum in 1988. It is currently in store, awaiting restoration once funds allow. Photo: https://beamishtransportonline.co.uk/transport-stocklist/buses/keighley-trolleybus-12/

Many of the problems that contributed to the early demise of Keighley Corporation’s tramway were clearly of its own making, but not all of them. The ageing infrastructure and newer competing technologies were much more systematic, which is why the British tramway industry had reached its peak by the early 1920s. The closure of Keighley’s tramway was the first of many more in following years, irrespective of who owned and operated them.

None of Keighley’s tramcars are known to have survived. The National Tramway Museum holds a collection of photographs relating to the tramway, and there are a number of publications including the following:

• J S King (1964), Keighley Corporation Transport (Advertiser Press)

• B M Marsden (2006), Keighley Tramways and Trolleybuses (Middleton Press)

• Trevor M Leach (1999), Trams and Buses of Keighley in Old Photographs (Hendon Publishing Co.)

• M Evans, Any More Fares? A Personal Recollection of Public Transport in Keighley

With thanks to Museum Volunteer Jim Dignan for producing this article.

Image References:

1-5: National Tramway Museum collection

6. T.M. Leach (1999), Trams and Buses of Keighley in Old Photographs (Hendon Publishing).

7. J.S. King (1964), Keighley Corporation Transport (The Advertiser Press Limited), p. 46; T.M. Leach (1999), Trams and Buses of Keighley in Old Photographs (Hendon Publishing).

8. National Tramway Museum collection

9. https://beamishtransportonline.co.uk/transport-stocklist/buses/keighley-trolleybus-12/