31st August 2024 marks 150 years since the opening ceremony conducted by Aberdeen District Tramways. This system began life as a 2¼-mile long horse tramway with just two routes, six tramcars and a depot at Queen’s Cross. From these small beginnings the network gradually expanded over the next two decades to reach a maximum extent of just under 12 miles by 22nd August 1896, by which time the fleet had expanded to some 40 horse trams.

As with virtually all of Britain’s early tramways, this was a company-owned system. Local authorities were not legally allowed to operate their own trams until 21 years had elapsed, at which point they were free to purchase the undertaking. Usually this was on highly favourable terms, as the valuation took account of depreciation of the assets over time.

Image 1: Postcard of an early Aberdeen District Tramways horse tram on one of the original routes, a circular from Queen’s Cross, via Albyn Place and Union Street to the North Church. Source: National Tramway Museum collection.

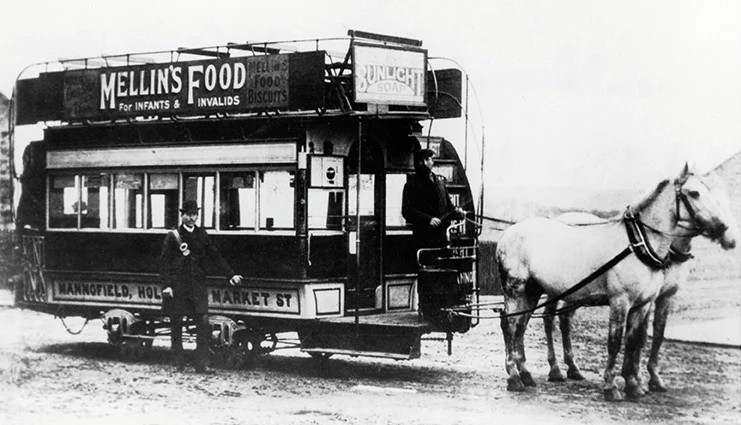

Drivers and conductors were paid just £1.10 (22/-) per week and were expected to work for 14½ hours per day. The horses normally worked in pairs for a 3½ hour shift but in adverse conditions 3 horses per tram were often needed. The average life of a tram horse was 5 years, and the average weekly cost of feeding each horse came to half the tram crew’s weekly wage at 60p (11/-).

The first tramcars were built by the Starbuck Car and Wagon Company but in later years (1883 onwards) a local manufacturer – R & J Shinnie – provided them. In the first year of operations, over a million passengers were carried at a time when the city’s population was approximately 90,000. However, the fare of 3d (just over 1p) for the full journey was probably beyond the means of most of its residents.

Image 2: One of the later Aberdeen horse trams, built by local manufacturer R & J Shinnie, on the Mannofield route, which opened in 1880. These were equipped with transverse seating on the upper deck, longer platforms and grab rails for added safety when boarding and disembarking. Source: https://doriccolumns.wordpress.com/welcome/aberdeen-city/tram-routes/

One of the biggest challenges facing the tramway, given its location in the north of Scotland and some steep gradients, was maintaining a regular service during the frequently harsh winter months. This gave rise to some novel solutions.

Adding a third horse was a routine response during the city’s frequent winter snowstorms, but when conditions put a stop to normal tramcar operations, a novel innovation in British public transport history was the ‘tram sledge’. These were introduced in December 1878 and consisted of simple wooden frames mounted on iron runners and equipped with knifeboard seats for 20 passengers. Although generally confined to tram routes, an additional service running from Market Street to University Road from 1879 was said to have been popular with students despite (or perhaps because of!) spills being commonplace. It is not known when they were used for the last time.

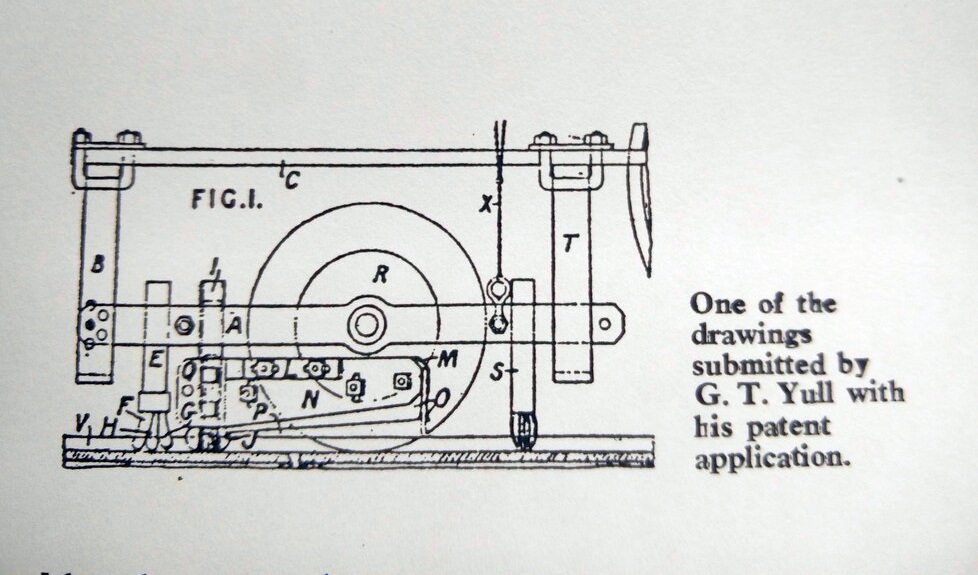

Another ingenious response to the problem took the form of a “Yull Patent Tramway Cleaner”, which was a heavily built cart fitted with tramway wheels that was drawn by up to four horses at a time. The mechanism involved a system of scrapers and gear-driven wire brushes that were intended to clear the snow from the tracks while a sanding device delivered sand to the part of the roadway used by the horses.

Image 3: One of the drawings submitted by G.T. Yull in support of his patent application. The drawing was published in M.J. Mitchell and I.A. Souter (1983), ‘The Aberdeen District Tramways’, published by N.B. Traction.

The device was said to have cleared 3 inches of hard-packed snow in George Street in 3 hours on its first outing in January 1875. However, problems persisted even when it was pulled in later years by a steam traction engine. Adding salt to the sand was a reasonably effective way of dealing with ice or light snow falls, but this gave rise to complaints about the effect it might have on the horses’ feet.

So concerned was one local resident – one James Ogston, of Norwood, Aberdeen – that, after written requests to stop the use of salt had failed, he issued legal proceedings to prevent the use of salt by the tramway company. After much legal to-ing and fro-ing the matter ended up in the House of Lords, the highest court in the land. In February 1896 it ruled that the practice constituted a nuisance and also awarded costs to Mr. Ogston.

The weather could be said to have had the last laugh, however, for later that year Aberdeen experienced a number of heavy snowfalls that blocked the tramway for several days. In the aftermath of further snowfalls in January 1897, the Council’s Cleansing Department deployed over 400 men and 230 carts on the mammoth task of clearing the snow. The tramway company’s staff joined in the endeavour because there was nothing else for them to do.

Episodes such as these provide a vivid indication of the drastic extent to which the climate has changed in the intervening 150 years! By this stage, however, the days of the tramways company itself were numbered. Just one month later, Aberdeen Corporation made an offer to buy out the company, which would result in the replacement of horse trams by much larger and more powerful electrically powered vehicles.

By 1902 all existing tracks had been electrified and the system continued to operate as the city’s principal public transport provider until 3rd May 1958. Almost immediately after the final day of operation, however, almost the entire fleet of tramcars was taken to the beach and unceremoniously burned, despite protests by members of the public.

Ironically, one of the tramcars that escaped this fate was one of the original Starbuck horse trams. One of thirteen horse trams to be taken over by the Corporation, it was converted to electric traction in 1902 and given the number either 61 or 63. In 1903 it was renumbered 57 and then, following its withdrawal from passenger service and conversion to a salt car, it was renumbered once more as 22.

Image 4: Restored Aberdeen horse tram ‘no. 1’ being drawn along Alford Place, possibly on the last day of tramcar operations. Source: https://doriccolumns.wordpress.com/welcome/aberdeen-city/tram-routes/

As long ago as 1924, this vehicle was converted back to its original form as a double deck horse tram. Ear-marked for use in tramway celebrations and, ultimately, for preservation, it was renumbered yet again (and erroneously) as number 1. In this guise it took pride of place in the ceremonial procession on Last Tram Day before ultimately finding a home in the Grampian Transport Museum in the village of Alford, 25 miles from Aberdeen.

Before then it was temporarily housed – and photographed by tramway enthusiasts – in a variety of locations including former tramway depots in Aberdeen and transport museums both north and south of the border before taking up permanent residence in Alford.

Image 5: Aberdeen no. 1 photographed by J H Price in Queens Cross depot in Aberdeen in 1955. Source: National Tramway Museum collection.

Image 6: Restored Aberdeen District Tramways ‘no. 1’ on display at the Grampian Transport Museum in Alford, Aberdeenshire. © Copyright Colin Smith and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

With thanks to Museum volunteer Jim Dignan for producing this article.

Further sources of information:

• The National Tramway Museum at Crich has various publications relating to the Aberdeen District Tramways Company and Aberdeen Corporation Tramways. The illustration of the line drawing depicting the Yull Patent Tramway Cleaner was taken from M.J. Mitchell and I.A. Souter’s The Aberdeen District Tramways, published by N.B. Traction 31, Forfar Road, Dundee.

• The Doric Columns website provides a remarkably detailed illustrated account of the history and heritage of the city of Aberdeen. It can be accessed at: https://doriccolumns.wordpress.com/

• Grampian Transport Museum: https://www.gtm.org.uk/

Image references:

1. National Tramway Museum collection.

2. https://doriccolumns.wordpress.com/welcome/aberdeen-city/tram-routes/

3. M.J. Mitchell and I.A. Souter (1983), The Aberdeen District Tramways, published by N.B. Traction.

4. https://doriccolumns.wordpress.com/welcome/aberdeen-city/tram-routes/

5. National Tramway Museum collection.

6. Copyright Colin Smith and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence